Global Governance 2020 - Designing the Future of International Institutions http://www.gg2020.net/

Here's a short sample of why we named our first book 2020: Our Common Destiny:

City of Hamilton - Planning & Economic Development

Vision 2020 Designations & Awards

http://www.hamilton.ca/ProjectsInitiatives/V2020/Awards/DesignationsAwards.htm

2020 Vision Exeter

http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=224685473481

Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2020

http://www.dbkl.gov.my/pskl2020/english/international_and_national_context_of_growth/index.htm

Charlotte Center City Partners

http://www.charlottecentercity.org/initiatives/plan/2/2020-vision-plan/

Casper, Wyoming's 2020 Vision

http://www.2020visionseeyourfuture.com/

Monte 2020

http://www.monte2020.org/

2020 Vision Campaign to eliminate nuclear weapons by the year 2020

http://www.2020visioncampaign.org/pages/495/Volgograd_marks_anniversary_of_Battle_of_Stalingrad_with_Mayors_for_Peace_Vision_for_the_future

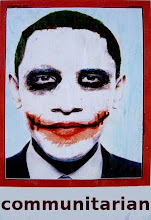

Global Implementation of Local Agenda 21Can Communitarian Global Governance work in Africa?

Mary Pattenden,

International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives

In 1992, world leaders gathered in Brazil at the United Nations Earth Summit and adopted Agenda 21, a global action plan for sustainable development. They also called on local authorities in each country to undertake a consultative process with their residents to establish a local version of Agenda 21 for their communities.

Since then, the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives has been working with local governments to develop methodologies and tools for Local Agenda 21 planning. This paper reviews the international progress being made and presents some of the lessons learned from early efforts to implement Local Agenda 21.

Source: http://www.peck.ca/nua/aif/aif03.htm

In June 1997, the United Nations held a Special Session of the General Assembly to evaluate world progress on the implementation of Agenda 21. When the UN Secretary General, tabled his report to the Special Session, entitled Overall Progress Achieved Since the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), it said: "Some of the most promising developments have taken place at the level of cities and municipalities, where local Agenda 21 initiatives have predominated.... Local-level strategies and plans have proved far more successful than those at the national level in terms of making a direct impact."

This recognition of local government achievement is well founded. The Local Agenda 21 Survey that was conducted in 1996 by the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), in conjunction with the UN Secretariat for the Commission on Sustainable Development, revealed that in the five years since the Earth Summit more than 1800 local governments in 64 countries had begun implementing Local Agenda 21 planning in their communities. As part of the process, these local governments are working together with local residents, community organizations, NGOs, businesses, unions, women, youth, and other stakeholders to develop and implement action plans for the sustainable development of their communities. They have been changing the structure and procedures for local governance along the way.

What is Local Agenda 21

Agenda 21, which was adopted by 178 countries at the UN Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, sets out a global action plan for sustainable development to deal with such areas of concern as poverty; human health, consumption patterns, demographic dynamics, protection of the atmosphere, land resource use, deforestation, desertification and drought, sustainable agriculture, biological diversity, management of biotechnology; protection of oceans, seas and coastal areas, protection of freshwater resources, toxic chemicals, hazardous waste, and solid wastes, sewage and sanitation issues. Agenda 21 states that many of these issues have their problems and solutions rooted in local activities and that the participation and cooperation of local authorities will play a critical role in the fulfillment of its objectives. Chapter 28 (see Appendix I) calls on local authorities in each country to undertake a consultative process with their populations and achieve a consensus on a local version of Agenda 21 for their communities.

When ICLEI first launched the Local Agenda 21 Initiative, in 1991, there were few models of participatory sustainable development planning available. Today there are dozens of examples of good practices, as well as guidelines, resource materials, planning models, and tools that local governments can use to implement the Local Agenda 21 process.

One of the most comprehensive efforts to develop models for Local Agenda 21 planning is ICLEI's Local Agenda 21 Model Communities Programme, which involved 14 cities and towns in 12 countries over a three-year period. In addition, ICLEI worked on projects with more than 170 local governments in 40 countries to apply the models and evaluate methodologies and tools for sustainable development planning.

This experience led to the development of a set of guidelines for Local Agenda 21 planning, that includes:the establishment of a multi-sectoral planning body or stakeholder group consisting of representatives from government, business, NGOs, women, youth and other constituencies to oversee the implementation of Local Agenda 21 planning;

the assessment of existing local social, economic and environmental conditions;

working through a participatory process to identify priorities for action for both the short-term and long-term;

the development and implementation of a multi-sectoral action plan for sustainable development with specific targets;

the establishment of monitoring and reporting procedures that hold the local government, business, and residents accountable to the action plan.

The application of such sustainable development processes challenges the traditional structures and procedures of local government. The requirement for integrated consideration of social, economical and environmental conditions challenges the municipal organizational structure of separate, and sometimes competing, disciplinary or function-based departments. The requirement for public participation and partnership approaches to problem-solving is inhibited by public-private sector role distinctions, lack of municipal recognition of informal communities, and traditional administrative culture. The requirement for the development and implementation of long-term strategies can be compromised by their lack of integration with the statutory development and planning that govern near-term municipal behavior. In short, effective Local Agenda 21 planning requires institutional reform to change the key investment and policy decisions of local governments.

Progress on Implementing Local Agenda 21

The majority of local governments that are actively involved in implementing guidelines for Local Agenda 21 have started with the reorganizations of their municipal structures and procedures. They have been creating new stakeholder organizations to involve their communities in the development and implementation of their action plans. They have also been re-shaping their institutional structures through the creation of inter-departmental planning units or the establishment of neighbourhood or village-level government units. For many this has resulted in profound changes to municipal structure and procedures.

For example, in 1993, the Province of Cajamarca, Peru, began its Local Agenda 21 process with the decentralization of the provincial government into 76 urban and rural jurisdictions, each with its own elected Mayor. It then worked with representatives from all sectors and jurisdictions, over the next three years, to produce a comprehensive sustainable development plan for six priority areas: Education; Natural Resources and Agricultural Production; Production and Employment; Cultural Heritage and Tourism; Urban Environment; and Women's Issues/Family And Population. Once the plan was developed and approved by the Provincial Assembly, it was then returned to local residents for a final endorsement in a referendum. (For more details see case summary Appendix II)

The re-organizational effort, in itself, does not produce concrete improvements in social, economic or environmental conditions. However, it lays the foundation for a more participatory and transparent process that works towards the development and implementation of an action plan supported by the community. It can broaden the resources of the local government to include the contributions of different sectors in the community.

Some municipalities have now completed the development of their Local Agenda 21 action plans and have begun full-scale implementation. These are mainly communities that had begun establishing the process, or specific components of it, before 1992.

For example, Hamilton-Wentworth, Canada, began using a multi-stakeholder approach to develop the Hamilton Harbor Remedial Action Plan and the Task Force on Affordable Housing, in the late 1980's. The success of these efforts led to the establishment of a participatory process for the sustainable development of the region. The first two-and-one-half years led to the production of a vision statement for the region, called Vision 2020, and to the production of 400 goals and recommendations. As the Vision 2020 was being implemented, Hamilton-Wentworth developed community-based indicators to measure progress. Each year, on Vision 2020 Sustainable Development Day, the community is presented with a Report Card on the progress of their sustainable community initiatives. (For more details see Appendix III)

As much as Local Agenda 21 activities depend on the voluntary support of the different sectors in the community, they are not small efforts or "amateur" endeavours. Rather, they are serious efforts to bring about change. In the wealthier countries, some local governments are putting substantial resources into the implementation process. For example, in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan a US $149 million budget was allocated for 52 projects. Initiatives to date include the construction of 100 "eco-housing" units which make use of rain water and recycled materials and are highly energy efficient. A Prefecture-wide system has been established to recover and destroy ozone depleting CFCs. The Prefecture has set a target to reduce consumption of tropical timber in public projects by 70% over a three-year period. (For more details see Appendix IV)

In developing countries, implementation tends to begin by addressing a few priority problems. For instance, the Local Agenda 21 effort in Quito, Ecuador is focusing on the stabilization and protection of the many ravines in that city's low income South Zone. The Local Agenda 21 effort in Santos, Brazil is establishing community solid waste management schemes in selected low income neighborhoods. In Jinja, Uganda the focus is on three priority areas - solid waste management, sewage and sanitation, and natural resources.

Common Elements of Success

Some communities have been more successful at implementing the process than others. When ICLEI's Model Communities Program studied some of the common characteristics of the more effective Local Agenda 21 processes, they included:

Beginning with a multi-sectoral partnership which includes all sectors

Identifying resources early in the processA resource commitment from the municipality to support the process

An explicit strategy for information sharing with local citizens.

Municipal respect for citizens' needs, priorities, and decisions

Involvement of both political leaders and municipal staff in the process

Not beginning the Local Agenda 21 process just before an election

Municipal alignment of policies and programs with the Local Agenda 21 process and action plan

The international Local Agenda 21 Survey revealed another dimension to the factors that influence the success of local governments in establishing this sustainable development process. Although the survey identified Local Agenda 21 activity in 64 countries, more than 80% of the activity was in the 11 countries with well-established national campaigns, including Australia, Bolivia, China, Denmark, Finland, Japan, Korea Republic, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In several of these countries more than half of local governments were implementing Local Agenda 21 processes.

For example, in the United Kingdom in 1993, the five local authority associations set up a joint Local Agenda 21 Steering Group to direct a campaign that would ensure a broad-based response by local government to Agenda 21. They established a multi-sectoral steering committee to direct the campaign, with representation by local elected officials, environmental NGOs, the business sector, women's groups, the educational sector, academia, trade union and the Local Government Management Board - LGMB. The LGMB, which is the technical agency of the local government associations, was established as the secretariat for the Campaign. The campaign supported local governments in their efforts by providing training, guidance, technical expertise, and opportunities for information exchange. As a result, more than 70% of local authorities in the UK have taken major steps towards undertaking Local Agenda 21 activities, on a voluntary basis. (For more details see Appendix V)

A typical national campaign is overseen by a multi-stakeholder steering committee that is staffed by the national association, with some campaigns having central government support. The campaign manages the recruitment effort, prepares guidance materials, organizes a series of training workshops, operates special projects on activities like indicators development, and liaises with the central government. In some countries the central government has regulated mandatory participation by local governments in the Local Agenda 21 process.

The most active region for Local Agenda 21 activity is Europe, both for the number of national campaigns and the number of cities involved. It also has the most active regional campaign, the European Campaign for Sustainable Cities & Town, which supports further national association involvement in Local Agenda 21 and the coordination of region-wide experience-sharing among participating municipalities and associations. In the book, From Earth Summit to Local Forum: Studies of Local Agenda 21 in Europe, Local Agenda 21 activity in eight countries was presented and the most significant characteristics supporting the implementation of Local Agenda 21 in these countries were identified, including: central-government initiatives and campaigns to disseminate information on Local Agenda 21; enough local-government autonomy to render the LA21 idea interesting and possible; and membership in cross-national environment-and-development alliances, charters. (For more details see Appendix VI)

In addition, at the international level, UN and donor agency programs have also field tested participatory action planning frameworks suitable for Local Agenda 21 implementation, with individual cities or groups of cities. The programs include the Sustainable Cities Programme of UNCHS, the Urban Environmental Guidelines Project of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), and the Rapid Urban Environmental Assessment Project of the Urban Management Programme.

The number of cities and towns embracing Local Agenda 21 planning is continuing to grow as national campaigns in 20 countries broaden their base of participation, and as regional and international campaigns supporting Local Agenda 21 practices recruit cities and towns worldwide. In addition, the APEC economies, have committed to doubling their Local Agenda 21 cities by the year 2003 in cooperation with ICLEI.

It is estimated that there are now more than 2000 local governments establishing the Local Agenda 21 process. At the same time as the numbers of local governments involved continues to grow, there is an expansion in the mandate for Local Agenda 21. This process, initially established to implement Agenda 21 at the local level, has now been recognized as a mechanism for the implementation of the Habitat Agenda . The Habitat Agenda is the global plan of action adopted at the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II), held in 1996, to deal with two goals: adequate shelter for all; and sustainable human settlements development in an urbanizing world.

Overcoming Obstacles to Success

If local governments are to be successful in their efforts to implement Local Agenda 21 processes, they will have to overcome local barriers to success, such as:traditional institutional structures that impede participatory decision-making or that are too linear for the complexities of sustainable development planning;

the influence of elections and new governments on the priority-setting process for the community;

the lack of general understanding of sustainable development principles and process by local elected officials, staff, and stakeholders in the community; and

the tendency for Local Agenda 21 processes to focus on traditional environmental policy and activities.

There are also a number of outside forces that can impede their success. Private market barriers such as those that do not require manufacturers to assume responsibility for the costs of disposing of the product packaging materials they use, can make it difficult for local governments to meet their targets - in this case related to waste management. Public markets barriers can encourage unsustainable behaviour - for example, business costs to provide employees with free automobile parking are tax deductible in some countries, while the costs for employers to provide public transit passes are not - a problem for cities trying to meet targets for greenhouse gas reductions and/or improved air quality. Legal and regulatory barriers can prohibit local governments from giving preferential treatment to developers who offer special measures to increase environmental or social benefits in their projects. Jurisdictional barriers can leave local governments with little or no authority to deal with local problems directly.

If Local Agenda 21 is to be implemented successfully, local government plans will need to be supported by national government policies and programs, and few existing Local Agenda 21 efforts are linked to national-level strategies. There are exceptions. In South Africa, for instance, Local Agenda 21 has been adapted as a mechanism to implement that country's Reconstruction and Development Plan. In Colombia, Local Agenda 21 is being linked to a major World Bank-funded, Ministry of the Environment project to improve the environmental management capacity of local governments.

In addition, implementation of the action plans that have been prepared by stakeholder groups will also require the integration of these plans into the separate, statutory planning processes of local government. This will require further local government reform. For example, in Hamilton-Wentworth, Canada, departmental staff are now required to demonstrate the consistency of any new proposed action with the community's "Vision 2020" action plan.

One other area of uncertainty is the relationship between Local Agenda 21 action plans and the global objectives of Agenda 21. Of necessity, a Local Agenda 21 must address local priorities as defined by the participatory process. While Local Agenda 21s in richer countries tend to include actions on issues such as climate change and the protection of global biodiversity, these issues may not receive much attention in communities of the developing world. However, the process does help to educate local residents about the linkages between local and global problems.

Conclusion

The primary success of the Local Agenda 21 movement to date has been to help build the prerequisite local institutional capacity for sustainable development in hundreds of communities and dozens of countries. This has been accomplished with surprisingly little external support from donor agencies and central governments.

The movement is now entering its second phase. This phase of development will be characterized by the expansion of Local Agenda 21 activities, worldwide, as regional and national campaigns continue to grow. It will also be characterized by the movement of the process beyond institutional restructuring towards the implementation of action plans dealing with concrete issues and targets. For this purpose, the local government community will need to organize new kinds of support both within their communities and at the sub-national, national and international levels.

The true test of the Local Agenda 21 process will be the impact it has at both the local and global levels. Existing national campaigns, in partnership with regional and international associations, have begun the development of models, tools and procedures for measuring the impacts and evaluating the overall performance of the Local Agenda 21 effort.

For its part, ICLEI is working on projects with local governments to develop the new models and tools needed for cities and towns to implement their Local Agenda 21 action plans and monitor their progress. At the same time, it is also strengthening the framework for its international Local Agenda 21 Campaign, and establishing regional Local Agenda 21 networks in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. These networks will work with national associations of local government and other country-level partners to provide information and support to national Local Agenda 21 programs. ICLEI will also continue to monitor the progress of Local Agenda 21 activity worldwide.

Mary Pattenden is the Director of Development for the International Council of Local Environmental Initiatives (for more information see Appendix VII). ICLEI was established in 1990 as the international environmental agency for local governments. It is a democratic association of local governments committed to sustainable development, with more than 300 members in 56 countries. It directs two international campaigns, the Local Agenda 21 Initiative and the Cities for Climate Protection Campaign. The ICLEI web site is at http://www.iclei.org. Its email address is iclei@iclei.org. Mary Pattenden can be reached at mpattenden@iclei.org.

References:

Brugmann, J., 1997, Local Authorities and Agenda 21, in Dodds, Felix (editor), UNED-UK, 1997, The Way Forward Beyond Agenda 21, Earthscan.

ICLEI,1996, The Local Agenda 21 Planning Guide: An Introduction to Sustainable Development Planning, Toronto, ICLEI/IDRC/UNEP.

ICLEI, 1997, Local Agenda 21 Survey: A Study of Responses by Local Authorities and their National and International Associations to Agenda 21.

ICLEI, CAG Consultants, UNDESA Division for Sustainable Development, 1998, Study on National Obstacles to Local Agenda 21.

Lafferty, William M., and Eckerberg, Katarina (editors), ProSus, 1997, From Earth Summit to Local Forum: Studies of Local Agenda 21 in Europe.

UNDPCSD/ICLEI, The Role of Local Authorities in Sustainable Development, New York, April, 1995.

APPENDIX I

AGENDA 21, CHAPTER 28

LOCAL AUTHORITIES' INITIATIVES IN SUPPORT OF AGENDA 21

PROGRAMME AREA

BASIS FOR ACTION

28.1.Because so many of the problems and solutions being addressed by Agenda 21 have their roots in local activities, the participation and cooperation of local authorities will be a determining factor in fulfilling its objectives. Local authorities construct, operate and maintain economic, social and environmental infrastructure, oversee planning processes, establish local environmental policies and regulations, and assist in implementing national and subnational environmental policies. As the level of governance closest to the people, they play a vital role in educating, mobilizing and responding to the public to promote sustainable development.

OBJECTIVES

28.2. The following objectives are proposed for this programme area:

By 1996, most local authorities in each country should have undertaken a consultative process with their populations and achieved a consensus on "a local Agenda 21" for the community;

By 1993, the international community should have initiated a consultative process aimed at increasing cooperation between local authorities;

By 1994, representatives of associations of cities and other local authorities should have increased levels of cooperation and coordination with the goal of enhancing the exchange of information and experience among local authorities;

All local authorities in each country should be encouraged to implement and monitor programmes which aim at ensuring that women and youth are represented in decision-making, planning and implementation processes.

Activities

28.3. Each local authority should enter into a dialogue with its citizens, local organizations and private enterprises and adopt "a local Agenda 21". Through consultation and consensus-building, local authorities would learn from citizens and from local, civic, community, business and industrial organizations and acquire the information needed for formulating the best strategies. The process of consultation would increase household awareness of sustainable development issues. Local authority programmes, policies, laws and regulations to achieve Agenda 21 objectives would be assessed and modified, based on local programmes adopted. Strategies could also be used in supporting proposals for local, national, regional and international funding.

28.4. Partnerships should be fostered among relevant organs and organizations such as UNDP, the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat) and UNEP, the World Bank, regional banks, the International Union of Local Authorities, the World Association of the Major Metropolises, Summit of Great Cities of the World, the United Towns Organization and other relevant partners, with a view to mobilizing increased international support for local authority programmes. An important goal would be to support, extend and improve existing institutions working in the field of local authority capacity-building and local environment management. For this purpose:

Habitat and other relevant organs and organizations of the United Nations system are called upon to strengthen services in collecting information on strategies of local authorities, in particular for those that need international support;

Periodic consultations involving both international partners and developing countries could review strategies and consider how such international support could best be mobilized. Such a sectoral consultation would complement concurrent country-focused consultations, such as those taking place in consultative groups and round tables.

28.5 Representatives of associations of local authorities are encouraged to establish processes to increase the exchange of information, experience and mutual technical assistance among local authorities.

MEANS OF IMPLEMENTATION

(a) Financing and cost evaluation

28.6. It is recommended that all parties reassess funding needs in this area. The UNCED Secretariat has estimated the average total annual cost (1993-2000) for strengthening international secretariat services for implementing the activities in this chapter to be about $1 million on grant or concessional terms. These are indicative and order-of-magnitude estimates only and have not been reviewed by Governments.

(b) Human resource development and capacity-building

28.7. This programme should facilitate the capacity-building and training activities already contained in other chapters of Agenda 21.

APPENDIX II

LOCAL AGENDA 21 IN CAJAMARCA, PERU

The Provincial Municipality of Cajamarca, Peru, ranks among the poorest communities in the world. In 1993, its infant mortality rate was 82% higher than the Peruvian national average. Cajamarca's main river has been polluted by mining operations and untreated sewage. Farming on the steep Andean hillsides, overgrazing, and the cutting of trees has resulted in severe soil erosion. Increasing poverty is a major concern. The lack of coordination between agencies made progress almost impossible.

In 1993, the Mayor of Cajamarca initiated an extensive LA21 planning effort for the Province. The effort had two components. The first was the decentralization of the provincial government into 76 jurisdictions, each with its own elected mayor, so that government decisions would reflect the needs of the Province's many small and remote communities. Cajamarca City was divided into 12 neighborhood Councils and the surrounding countryside into 64 "minor populated centers", each with their own elected Mayors and Councils. The second component was the creation of a Provincial Sustainable Development Plan through a three-year participatory process.

The Provincial Council established new partnership structures, which for the first time included a wide range of stakeholders, including private and public institutions, local communities, farmers, entrepreneurs, and state and national government organizations. The initiative, known as the Inter-Institutional Consensus Building Process, aimed for broad-based consensus on projects that would form the basis for a Provincial Sustainable Development Plan.

Six "Theme Boards" were established to develop action proposals in the following areas: Education; Natural Resources and Agricultural Production; Production and Employment; Cultural Heritage and Tourism; Urban Environment; and Women's Issues, Family, and Population. A larger Inter-Institutional Forum provided an opportunity for discussing proposals among all the Theme Boards.

The plans prepared by the Theme Boards were integrated into a Provincial Sustainable Development Plan, which was submitted to the Provincial Council in August, 1994. Having received approval, after a series of public education workshops about the Plan, the Plan was submitted for public approval through a citizens' referendum.

APPENDIX III

LOCAL AGENDA 21 IN HAMILTON-WENTWORTH, CANADA

The Regional Municipality of Hamilton-Wentworth, Canada: Hamilton-Wentworth is situated on the western shores of Lake Ontario and consists of a highly industrialized core surrounded by rural communities. While the perception of the region is one of smokestacks and industry, the area also encompasses a large number of natural features, and environmentally sensitive areas.

Hamilton Harbour was considered one of the most extreme "toxic hot spots" in the Great Lakes system. In 1986, the community established a multi-stakeholder roundtable, which included representatives from industry, the community, environmental groups, government, and other organizations, to identify the environmental problems in the harbour area and develop solutions for addressing them. The effort led to a pronounced improvement in harbour conditions.

The success of this project, plus other participatory efforts encouraged the community to take on the larger challenge of sustainable development of the region. In 1990, the Regional Council created a Citizens' Task Force on Sustainable Development charged with the mandate to consult with the public to develop an overall vision to guide future development of the region. The two-and-a-half year process involved more than a thousand citizen and resulted in a community vision called VISION 2020. The process also produced 300 detailed recommendations for VISION 2020, highlighting eleven key areas of concern, including natural areas and corridors, improving the quality of water resources, improving air quality, reducing the amount of waste, consuming less energy, land use in the urban area, changing modes of transportation, personal health and well-being, community empowerment, the local economy, and agriculture and the rural economy.

As the region began the implementation of VISION 2020, the Sustainable Community Indicators Project was also established involving the region, ICLEI, the Health of the Public Project, and McMaster University's Environmental Health Programme. The mandate of this project was to develop a monitoring system for VISION 2020 that was community driven and community oriented. This effort resulted in the development of a set of twenty-nine indicators to monitor overall community progress. Each year progress on Vision 2020 is reported to the public on Annual VISION 2020 Sustainable Community Day.

APPENDIX IV

LOCAL AGENDA 21 IN KANAGAWA PREFECTURE, JAPAN

In 1993, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan adopted a civic charter for global environmental protection, called the Kanagawa Environment Declaration, as well as a local action plan called Agenda 21 Kanagawa. Agenda 21 Kanagawa was developed through an intensive process of dialogue that involved thousands of local residents and businesses, as well as the local authorities within Kanagawa.

Kanagawa Prefecture is the home of some eight million residents who live primarily in the Yokohama and Kawasaki metropolitan areas in the eastern part of the Prefecture along Tokyo Bay. With a gross domestic product equivalent to that of Sweden, Kanagawa is also one of the most highly industrialized regions of the world. Through its policies and actions, the Prefecture and its local municipalities can have an impact on the global environment.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the Prefecture became aware that the focus of environmental concern had shifted away from end-of-the-pipe industrial pollution problems to the more complex and non-point source issues of consumer lifestyles, the structure of urban space, and the gradual loss of natural lands to urbanization. Furthermore, the impact of local activities on the global environment, as demonstrated by Kanagawa's contribution to the ozone depletion problem, played a part in this changing awareness.

Agenda 21 Kanagawa was formulated by a new Interdepartmental Liaison and Coordination Committee, made up of the heads of every department within the Prefecture and chaired by the Vice Governor. A working level committee made up of section chiefs from each department was established to review detailed proposals. A secretariat within the Environment Department managed the public consultation and internal review processes.

Public input was provided through three sectoral "conferences" or committees: one for citizens and non-governmental organizations, one for private enterprise, and one for local municipalities in Kanagawa. In addition, neighborhood consultative meetings were organized and a direct mail package and questionnaire was sent to thousands of residents.

The final Agenda 21 Kanagawa is a detailed and comprehensive document. The FY 1994 budget for the 52 environmental protection projects implemented within the framework of the Agenda totaled U.S.$149 million. Initiatives to date include the construction of 100 "eco-housing" units which make use of rain water and recycled materials and are highly energy efficient. A Prefecture-wide system has been established to recover and destroy ozone depleting CFCs. Subsidies are provided for the purchase of non-CFC equipment. The Prefecture has set a target to reduce consumption of tropical timber in public projects by 70% over a three-year period, and is working with the local construction industry to reduce the widespread practice of using such timber for concrete moldings.

In terms of management reforms, a new Kanagawa Council for Global Environmental Protection has been established to continue the inter-departmentalism initiated through the Local Agenda 21 development effort. Finally, in each prefectural section an individual employee has been assigned to manage in-house environmental performance and to educate prefectural staff.

APPENDIX V

THE LOCAL AGENDA 21 NATIONAL CAMPAIGN IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

In January 1993, the five local authority associations in the United Kingdom (the Association of district Councils, the Association of Country Councils, the Association of Metro Authorities, the confederation of Scottish Local Authorities and the Association of Local Authorities in Northern Ireland) set up a joint Local Agenda 21 Steering Group to develop and direct a campaign aimed at ensuring a broad-based response by local government to Agenda 21.

They established a multi-sectoral steering committee to direct the campaign, with representation by local elected officials, environmental NGOs, the business sector, women's groups, the educational sector, academia, trade union and the Local Government Management Board - LGMB. The LGMB, which is the technical agency of the local government associations, was established as the secretariat for the Campaign.

For their first task, the steering group defined the substantive elements of Local Agenda 21 in the UK context:

managing and improving municipal environmental performance;

integrating sustainable development into municipal policies and activities;

awareness-raising and education

public consultation and participation;

partnership-building;

measuring, monitoring, and reporting on progress towards sustainability.

The campaign supported local governments in their efforts to address these areas by providing training, guidance, technical expertise, and opportunities for information exchange. As A result, more than 60% of the local authorities in the UK have taken major steps towards undertaking Local Agenda 21 activities. The initiative has been a way to strengthen local authorities' commitments to the environment, economic and social development, and local democracy.

Through the UK Local Agenda 21 Campaign, the UK local authority association has quickly and voluntarily made Local Agenda 21 a part of everyday business for the majority of UK local authorities. The high rate of success in such a short period of time can be explained by the importance of national municipal associations, the role of the Steering Group members and their respective networks in influencing local authorities, and the readiness of the local authorities themselves to take a leadership role in sustainable development.

APPENDIX VI

Study of Local Agenda 21 Implementation at the National Level

The most active region for Local Agenda 21 activity is Europe both for the number of national campaigns and the number of cities involved. In the book, From Earth Summit to Local Forum: Studies of Local Agenda 21 in Europe, the editors presented descriptions and analysis of Local Agenda 21 activity in eight countries, including Austria, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Norway, Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The conclusions of this report include a list of the most significant characteristics affecting the successful implementation of Local Agenda 21, based on their study, including:

A previous involvement on the part of representatives of local authorities in the UNCED process

An active positive attitude on the part of responsible central-government official to the LA21 idea

Central-government initiatives and campaigns to disseminate information on Local Agenda 2

The availability of central government financial resources to subsidize LA21 initiatives

Enough local-government autonomy to render the LA21 idea interesting and possible

Membership in cross-national environment-and-development alliances and charters

A previous history of international "solidarity' orientations and activities at the local level

Previous municipal involvement in environmental and sustainable-development pilot projects

Previous experience with 'co-operative management regimes' (among social partners and stakeholders

Active individual 'firebrands' for LA21 at the local level

Perceived possibilities for coupling LA21 with the creation of new jobs

Perceived conditions of 'threat' to local environment-and -development conditions from external sources.

The book, From Earth Summit to Local Forum: Studies of Local Agenda 21 in Europe was edited by William M. Lafferty Professor of Political Science, University of Oslo, and Director, Programme for Research and documentation for a Sustainable Society (ProSus), Norway and by Katarina Eckerberg, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Umea , Sweden for the Program for Research and Documentation for a Sustainable Society Research Council of Norway, Oslo (ProSus).

APPENDIX VII

INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR LOCAL ENVIRONMENTAL INITIATIVES (ICLEI)

The International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) is an association of local governments dedicated to the prevention and solution of local, regional, and global environmental problems through local action.

ICLEI was established in 1990 as the international environmental agency for local governments under the sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, International Union of Local Authorities (IULA), and the Center for Innovative Diplomacy. It is a democratic association with more than 300 members - cities, towns, counties and their associations in 56 countries - committed to sustainable development. Each member holds a position on the ICLEI Council.

In its extensive work with local governments, ICLEI has established two worldwide programs that are crucial to the implementation of sustainable development worldwide:

The Local Agenda 21 (LA21) Initiative supports local governments in the preparation and implementation of sustainable development action plans. There are now more than 2,000 local governments in 64 countries engaged in LA21 planning.

The Cities for Climate Protection (CCP) Campaign works with more than 250 cities in 41 countries to establish and implement concrete actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These activities also improve local air quality and urban livability.

ICLEI supports these programs with comprehensive research, pilot projects, technical expertise, capacity building, small incentive grants, resource materials, and a world wide web site at . In addition, ICLEI provides an extensive international training and exchange program for local government representatives - to date more than 8,000 have participated in ICLEI's networking and training activities.

ICLEI is well situated to provide international projects with local government contacts in more than 50 countries. Its activities are carried out through affiliated nationally incorporated not-for-profit companies in Canada, the USA, and Germany, as well as through a partner organization in Japan. The World Secretariat is in Toronto, Canada. The European Secretariat and International Training Centre is in Freiburg, Germany. It has offices in Berkeley, USA; Tokyo, Japan; Harare, Zimbabwe; and Santiago, Chile.

"Global Governance Initiative A Critique of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD)" byLaura Schell-Kerr, Carleton University, Department of Political Science, MA Candidate http://www.forumfed.org/FedGov/archives/volume6/FG_VOL6_ISS1_SCHELL-KERR.pdf

4 comments:

Obviously global governance is bad, but you never talk about whether or not sustainability is good or even necessary. If, just hypothetically at least, sustainability is a necessity for the survival of the human race, how will it be done?

Global governance is not obviously bad to the many people out there who support the idea. By 2020 we will have a massive complex global government, and then we'll all see what kinds of sacrifices must be made in the name of sustainability.

If sustainability were necessary to the survival of the human race, then the communitarians would have to retrain 10 % and kill off 90% of the human population, just as they say they must. Sustainable Development is predicated on the idea that we humans cannot use the resources on the planet to survive because it destroys the planet. This is just a slick plan to steal all the resources and kill off all the non compliant people who live on the land. But who can believe such a thing, eh? It's so terrible it can't possibly be true. And if it were true, Fox news would tell us.

People are such suckers, they buy into the whole SD concept without ever asking about the foundation or philosophy behind it. If the theory for SD is a con then SD is a con, so let's make sure we never discuss the theory, right?

Sustainable Development did not arise naturally, but sound management of natural resources is and always has been vital to people connected to their natural environment. To the reasonable local who wants to live healthy, the compelling Utopian concept of global sustainability is appealing because it appears to address core problems with modern pollution. But Sustainable Development is not about protecting and preserving the Earth, it's about taking control over everything in the name of the new global religion, and the only way to discover that is to study comprehensive plans.

To see what's hidden in the SD concept requires too much reading and study for most people, which is why I post these long excerpts from places like ICLEI, because I want my readers to be somewhat exposed to "expert" presentations that support the plans.

Plus, to me anyway, the very idea that one ideology can save the entire human race raises the opposite (Hegelian) possibility that one collective ideology can destroy the entire human race.

If globally managed sustainability is such a good idea, why does it have to be introduced in such a devious, illegal way?

Thanks! Two more questions:

1. Do you think global governance is an inherently flawed idea? The reason I ask this is, there are a lot of people who don't really care about national sovereignty purely out of humanist idealism. They see a global government as the rational next-step in terms of facilitating peace and prosperity for the entirety of humanity. Is that fundamentally impossible? When you talk about global government, you're automatically implying global tyranny without addressing the popular preconceived notion that a global government would or could be some kind of global democratic utopia. Put simply: What do you have to say to Star Trek fans who desire a global government that is not some kind of totalitarian bankster eugenicist wage-slavery ass-fucking?

2. What do you think of the "tragedy of the commons" and, if it were a valid phenomenon, how would you imagine to reconcile it with individual property and consumption rights?

In my opinion, while your research has been... extremely thorough, you guys have unfortunately done a very poor job at explaining the implications of communitarianism and Agenda 21 in a clear and understandable way. Your writings have been absolutely muddled with excessive details and obscure theory, best consumed AFTER you have a basic general understanding.

All of this needs to be explained in every important, meaningful way, immediately understandable to basically anyone who can read, regardless of their world view in only one paragraph. Not a giant page, not an article, not a book, one paragraph. DO NOT USE THE WORD "DIALECTIC" IN IT. It can be done and I wish you would do it. I don't care if you care about trying to convince people anymore or not. Other people want to convince people, but they need the tools to do it. You understand the subject better than basically anyone and you need to be the one to do this.

Yes, for what it's worth, I think global governance is a bad idea.

I don't have time to have an opinion of the "tragedy of the commons." Sorry.

As for the assumption that I "need" to find a way to describe it for all levels of readers in one easy paragraph, well, if I could have done it, don't you think I would have written that one, simple, perfect graph by now?

Why don't you give it a try? Maybe all it will take to accomplish it is a fresh perspective.

One of the reasons I stopped caring about convincing people was because they were too lazy to contribute anything themselves, they just kept asking me for more.

But yeah, I wish I had that perfect graph as much as you do. Please, write it for all of us. And use any words you choose. :)

Post a Comment